You Can’t Think Your Way Out of Trauma: Why Your Body Holds the Key to Emotional Healing

From Your Kind of Hapy LLC.

The Paradox of Understanding Without Relief

Sarah sat across from me in our third therapy session, visibly frustrated. “I know I’m safe now,” she said, her hands clenched in her lap. “I know he can’t hurt me anymore. I know my reaction is irrational. So why do I still feel this way?”

She had done everything right. She’d read the books on trauma recovery. She could articulate her cognitive distortions with textbook precision. She understood, intellectually, that her past didn’t define her future. Yet every time her phone buzzed unexpectedly, her heart would race. Every time she heard footsteps in the hallway, her muscles would tense. Every time she tried to relax, her body would scream danger.

Sarah’s struggle represents one of the most misunderstood aspects of emotional healing: the assumption that insight equals relief. In clinical practice, I encounter this paradox constantly — patients who can analyze their feelings with remarkable clarity but can’t seem to change them. They believe that if they could just think correctly, feel correctly, or understand deeply enough, the anxiety, panic, or hypervigilance would disappear.

They’re trying to think their way out of emotions that were never thought into existence.

This article explores why cognitive approaches alone often fail after trauma, when body-based interventions become essential, and how integrating both creates a more complete path to healing. Understanding this distinction has transformed my clinical work and offers hope for anyone who’s ever wondered why they can’t “just get over it.”

The Architecture of Emotion: Body First, Mind Second

Here’s what most people don’t realize: emotions are physiological events before they become psychological experiences.

When you encounter a stressor, your body responds in milliseconds. Your amygdala — the brain’s threat-detection center — activates before your conscious mind has even identified what’s happening. Your heart rate increases. Stress hormones flood your system. Your muscles prepare for action. Blood flow redirects from your digestive system to your limbs. Your pupils dilate. Your breath becomes shallow.

Only then does your prefrontal cortex — the thinking, reasoning part of your brain — get involved to name and interpret the experience.

This sequence matters profoundly. As neuroscientist Antonio Damasio documents in his research on somatic markers, our bodies generate feelings first, and our conscious minds create stories about those feelings second (Damasio, 1994). The breath, muscles, heartbeat, and gut communicate directly with the emotional brain through the vagus nerve and other pathways, creating what we experience as “feelings” before language, logic, or analysis enter the picture.

You can reason all you want, but logic cannot override a body that believes it’s in danger.

This isn’t a flaw in the system — it’s a feature. The body’s ability to respond to threats faster than conscious thought has kept our species alive for millennia. But it creates a significant challenge for modern emotional healing: the very architecture of emotion means that purely cognitive approaches will always be incomplete.

When Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Works (And When It Doesn’t)

I want to be clear: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is one of the most empirically supported treatments in psychology. It works remarkably well for specific types of problems. But understanding when and why it works reveals its limitations.

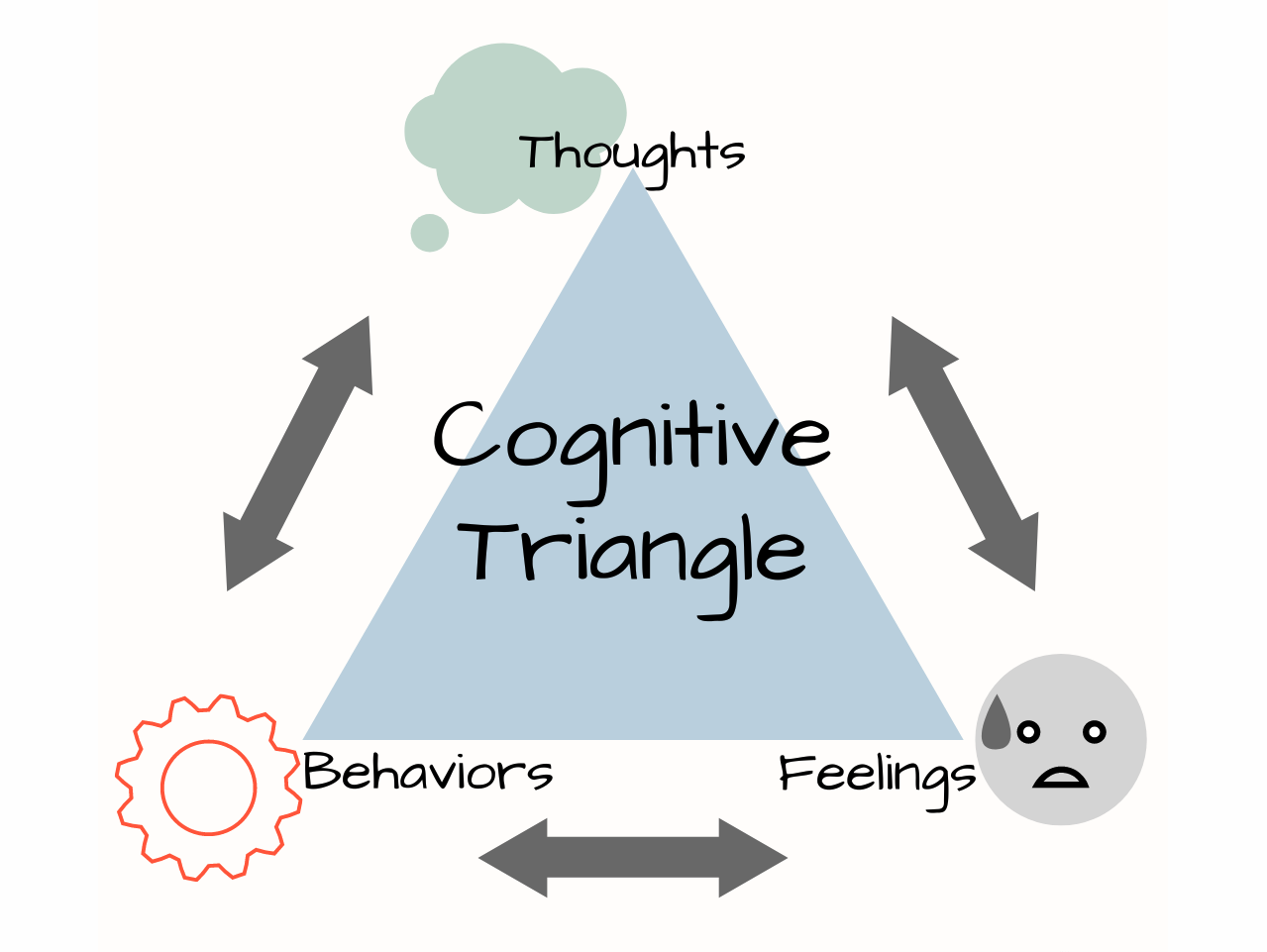

CBT excels when the problem originates in the mind — when maladaptive thoughts create emotional responses. The classic CBT model looks like this:

Situation → Thought → Emotion → Behavior

For example: Your colleague makes a critical comment at work. You think, “They hate me and think I’m incompetent.” This thought generates anxiety and shame. You avoid future meetings, reinforcing the belief.

In this sequence, the thought is genuinely creating the emotional problem. Challenge the thought (“Maybe they were having a bad day, and this wasn’t about me”), and the emotion shifts. Develop a more balanced interpretation (“I can receive feedback without it defining my worth”), and the behavioral pattern changes.

This works beautifully for everyday stressors, future-oriented worries, and situations where you first think, then feel. CBT helps you identify cognitive distortions, generate alternative interpretations, and behave as if the healthier thought is true until your emotional brain catches up.

But in my practice, I found this strategy failing repeatedly with certain patients. They could identify their distortions. They could generate rational alternatives. They’d practice thought records and behavioral experiments diligently. Yet the anxiety, panic, or hypervigilance persisted.

It took me several years to understand what was really happening: You cannot think your way out of an emotion-based problem that’s rooted in trauma.

The fundamental issue is that trauma rewires the sequence. Instead of:

Thought → Emotion

Trauma creates:

Body Sensation → Emotion → (Later) Thought

The emotion isn’t being generated by a maladaptive thought that can be challenged. It’s being generated by a dysregulated nervous system responding to perceived threat — often without any conscious thought involved at all.

This realization led me to distinguish between top-down therapeutic approaches (starting with the mind, like CBT) and bottom-up approaches (starting with the body, like Somatic Experiencing, EMDR, or neurofeedback). The critical clinical skill isn’t choosing one over the other — it’s knowing which to use when.

The Neurobiology of Trauma: Why the Body Keeps the Score

To understand why trauma requires body-based intervention, we need to understand what trauma actually does to the brain and nervous system.

Dr. Bessel van der Kolk’s seminal work, The Body Keeps the Score, synthesizes decades of trauma research into a clear picture: trauma fundamentally alters how the brain processes threat and safety (van der Kolk, 2014). These changes aren’t “all in your head” — they’re measurable, observable shifts in brain structure and function.

The Thinking Brain Goes Offline

During overwhelming stress or trauma, the prefrontal cortex — responsible for executive function, rational thought, and impulse control — effectively goes offline. Brain imaging studies show decreased activation in this region during trauma recall. Meanwhile, the limbic system, which governs emotion, memory, and survival responses, becomes hyperactive.

This isn’t a choice or a weakness. It’s adaptive biology. When your ancestors encountered a predator, stopping to rationally analyze the situation would have been fatal. The brain evolved to bypass slow, deliberate thinking in favor of fast, automatic survival responses: fight, flight, freeze, or fawn.

The problem emerges after trauma, when this protective mechanism becomes stuck in the “on” position.

The Body Becomes a Perpetual Threat Detector

After trauma, the nervous system recalibrates. The threshold for perceiving danger drops dramatically. The body becomes hypervigilant, constantly scanning for threats even when objectively safe. This isn’t paranoia or catastrophizing — it’s a physiological state called autonomic dysregulation.

Dr. Stephen Porges’s Polyvagal Theory explains this phenomenon through the vagus nerve, which acts as a communication highway between the body and brain (Porges, 2011). After trauma, this system can become stuck in a state of sympathetic activation (fight/flight) or dorsal vagal shutdown (freeze/collapse), making it extraordinarily difficult to access the ventral vagal state associated with safety and social connection.

Even mild stressors — a loud noise, an unexpected touch, a certain tone of voice — can trigger the same full-body alarm response as the original trauma. The person’s cortex might know they’re safe. Their body hasn’t received the message.

This is why Sarah could understand intellectually that she was safe while simultaneously experiencing panic attacks. Her prefrontal cortex possessed accurate information. Her amygdala and autonomic nervous system were still responding to a threat that ended years ago.

Trauma Is Stored as State, Not Just Narrative

Perhaps most importantly, trauma isn’t stored primarily as a verbal memory or narrative that can be processed through talk therapy alone. It’s encoded as a somatic state — patterns of muscle tension, breath restriction, heart rate variability, and hormonal responses.

Dr. Peter Levine, founder of Somatic Experiencing, describes trauma as incomplete biological responses to threat (Levine, 2010). When fight or flight is thwarted, the autonomic arousal energy remains trapped in the body, creating chronic tension, hypervigilance, and dysregulation.

This is why trauma therapy must always include bottom-up regulation — interventions that work directly with breath, sensation, movement, and nervous system states. Once the body begins to discharge this trapped activation and recalibrate to safety, then top-down approaches like cognitive restructuring and narrative integration become effective.

Trying to do the reverse — thinking your way out while the body remains alarmed — only deepens the disconnection between mind and body. It’s like trying to read a map during an earthquake. The information might be accurate, but the ground is still shaking.

The Clinical Framework: Matching Intervention to Problem Type

Understanding the distinction between mind-originating and body-originating emotional experiences creates a practical clinical framework. The key question isn’t whether to use cognitive or somatic approaches — it’s when to use which.

When to Start with the Body (Bottom-Up First)

If you feel flooded — racing heart, tight chest, shallow breath, mind going blank, or overwhelming emotion — start with the body.

These signals indicate that your nervous system is in a state of activation or shutdown. Your prefrontal cortex is offline or barely functioning. Cognitive interventions won’t work because the part of your brain that can process them isn’t accessible.

The goal at this stage isn’t insight, understanding, or reframing. It’s regulation — bringing the nervous system back to a state where thinking becomes possible again.

Body-first interventions include:

Sensory Grounding: The fastest way to orient your nervous system to present safety is through immediate sensory input. Look around the room slowly and intentionally. Name five things you can see, four things you can hear, three things you can touch, two things you can smell, one thing you can taste. This practice, rooted in dialectical behavior therapy, interrupts dissociation and reorients attention to the here-and-now.

Breath Regulation: The vagus nerve, which controls parasympathetic calm, responds directly to breathing patterns. Specifically, extending the exhale longer than the inhale signals safety to the nervous system. Try breathing in for a count of four, holding for four, and exhaling for six or eight. This isn’t about “calming down” through force of will — it’s about using physiology to shift physiology.

Movement and Discharge: Trauma creates bound-up activation energy in the body. Gentle movement helps discharge it. Shake out your arms and legs. Roll your shoulders. March in place. Stand up and stretch. Push against a wall. These aren’t exercises — they’re ways of completing the biological impulse to move that may have been thwarted during the traumatic experience.

Orienting to Space: In trauma states, peripheral vision narrows and attention becomes hypervigilant. Deliberately practicing orienting — gently turning your head left and right, allowing your eyes to track around the space, noticing windows, doorways, and exits — helps the nervous system recognize that you’re not trapped and the environment is navigable.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation: Systematically tensing and releasing muscle groups brings awareness to where tension is held and provides a release pathway. Start with your feet, squeeze for five seconds, release completely, and notice the difference. Move up through calves, thighs, abdomen, hands, arms, shoulders, neck, and face.

When these interventions work, you’ll notice physiological shifts: breath deepens naturally, shoulders drop, jaw unclenches, hands warm up, peripheral vision expands. These changes signal that your nervous system is downshifting from threat response back toward a window of tolerance where thinking becomes possible again.

That’s when cognitive tools start working.

When to Bring in the Mind (Top-Down Second)

Once you’re regulated enough to think about the feeling instead of from it, cognitive processing becomes not just possible but powerful.

Signs you’re ready for cognitive work:

You can take a full, deep breath

You can maintain attention on what someone is saying

You can access multiple perspectives

You notice some space between stimulus and response

Your body feels somewhat settled, even if emotions remain

Mind-focused interventions include:

Precise Emotional Labeling: Research by psychologist Matthew Lieberman shows that simply naming emotions with specificity reduces amygdala activation (Lieberman et al., 2007). Instead of “I feel bad,” practice distinguishing: “This is grief, not anger.” “This is anxiety about the future, not danger in the present.” “This is shame about my response, not the original event.” Precision matters because different emotions require different responses.

Fact-Checking the Threat: Once regulated, you can engage your prefrontal cortex to evaluate reality. Ask: “Is the danger happening right now, or is this an old alarm system firing?” “What’s the actual evidence for this belief?” “What would I tell a friend experiencing this?” This isn’t about dismissing feelings — it’s about distinguishing between real present danger and echoes of past danger.

Meaning-Making and Reframing: Trauma often creates harmful narratives: “I’m broken.” “It was my fault.” “I should have been able to prevent it.” Once regulated, you can begin examining these stories with compassion. “My reaction makes complete sense given what I’ve lived through.” “My body was trying to protect me with the resources it had.” “Survival isn’t the same as healing, and I’m learning to heal now.”

Values Identification: When caught in emotional overwhelm, we lose connection to what matters most. Reconnecting to values provides direction. “What do I want to stand for in this moment?” “What kind of person do I want to be, regardless of how I feel?” “If I were acting from my wisest self, what would I do next?”

Narrative Integration: Eventually, trauma can be integrated into a coherent life story rather than remaining a fragmented, intrusive set of sensations. This is the work of meaning-making — not erasing what happened, but placing it within a larger context of resilience, growth, and identity. This happens last, after regulation and cognitive restructuring have created a stable foundation.

The Essential Sequence:

Regulate → Reflect → Reframe

This progression — moving from body regulation to cognitive reflection to meaning reframing — mirrors the brain’s natural recovery pattern after stress. The body must downshift from threat response before the mind can accurately evaluate information and before narrative integration becomes possible.

Trying to skip steps creates problems. Attempting cognitive reframing while dysregulated usually fails and often increases shame (“Why can’t I think my way out of this?”). Staying only in body regulation without ever integrating cognitively can limit growth and meaning-making.

The art of trauma-informed therapy is learning to move fluidly between bottom-up and top-down, matching the intervention to the person’s current state rather than applying a one-size-fits-all approach.

A Practical Decision Matrix for Daily Life

Understanding theory matters, but application matters more. Here’s a practical framework you can use to determine which approach you need in the moment:

From Your Kind of Happy LLC.

The pattern remains consistent: When the body is activated, calm the body first. When the body is calm, engage the mind.

Common Mistakes in Trauma Recovery

Understanding this framework also illuminates common mistakes that delay healing:

Mistake #1: Forcing Cognitive Work During Activation

Many therapy approaches jump straight to “processing” trauma through talking, analyzing, or reframing while the person remains physiologically activated. This not only fails but can retraumatize by creating repeated exposure to overwhelming sensations without the regulation skills to manage them.

What works instead: Establish regulation skills first. Practice them in neutral or mildly stressful situations before attempting trauma processing. Build a toolkit of bottom-up interventions that work specifically for you.

Mistake #2: Avoiding Cognitive Integration

On the opposite end, some people become so focused on nervous system regulation that they avoid the necessary cognitive and narrative work. They can calm their body but never examine the beliefs, meanings, or behavioral patterns that keep them stuck.

What works instead: Once you have reliable regulation skills, gradually work toward cognitive processing and meaning-making. This might look like journaling, therapy focused on beliefs and identity, or creative expression that helps integrate the experience.

Mistake #3: Interpreting Body Signals as Personal Failure

Perhaps the most damaging mistake is interpreting your body’s protective responses as evidence that you’re broken, weak, or failing at recovery. The belief “I should be over this by now” adds shame on top of existing distress.

What works instead: Recognize that your nervous system is doing exactly what it evolved to do — protect you. The hypervigilance, the startle response, the avoidance aren’t character flaws. They’re adaptations. The goal isn’t to eliminate your body’s protective mechanisms but to update them with new information about present safety.

Mistake #4: Using Only Insight Without Action

Understanding why you feel a certain way provides relief initially, but insight alone doesn’t create lasting change. Neuroplasticity — the brain’s ability to rewire — requires repeated experience of new patterns, not just intellectual understanding.

What works instead: Pair insight with action. Practice new responses repeatedly. Create situations where you can experience corrective emotional experiences — moments where the expected danger doesn’t materialize, where connection feels safe, where your body learns that it can be vulnerable without catastrophe.

Integration: Where Body and Mind Meet

The ultimate goal isn’t to privilege body over mind or vice versa. It’s integration — helping body and mind work together as they were designed to.

The body tells the truth of what has been experienced. It holds the visceral memory of threat, the patterns of protective response, the physiological imprint of overwhelm. This isn’t something to override or ignore — it’s wisdom.

The mind provides language, context, and meaning. It can create narratives that make sense of experience, identify patterns across situations, plan for the future, and generate hope. This isn’t weakness or overthinking — it’s also wisdom.

One regulates. The other integrates. Both are necessary.

When patients learn this sequencing, something profound shifts. They stop feeling broken for not being able to “just think differently.” They stop interpreting their body’s signals as betrayal or sabotage. They discover that their body wasn’t working against them — it was working tirelessly to protect them, sometimes with outdated information about what safety looks like.

The path forward begins when we stop fighting the body’s intelligence and start listening to it. When we honor the protective responses that kept us alive even as we gently update them with new information. When we recognize that healing isn’t about choosing mind over body or body over mind — it’s about reuniting them.

Actionable Steps: Building Your Personal Framework

Step 1: Identify Your Pattern

Over the next week, when you experience strong emotion, pause and notice: Did this start with a thought (“I think…therefore I feel…”) or a body sensation (“I suddenly felt…then I started thinking…”)?

Keep a simple log:

What triggered the feeling?

Where did you notice it first? (body or thought)

What was your automatic response?

This awareness builds the foundation for knowing which intervention you need.

Step 2: Build Your Regulation Toolkit

Experiment with different body-based regulation techniques. Not everything works for everyone. Some people respond to breath work, others to movement, still others to sensory grounding.

Try each technique below in a moment of mild stress (not during crisis):

4–7–8 breathing (inhale 4, hold 7, exhale 8)

Bilateral stimulation (tapping alternating knees)

Cold water on face or ice cube in hand

Notice which ones create a felt sense of settling in your body. Those become your go-to tools.

Step 3: Practice the Sequence in Low-Stakes Situations

Don’t wait for crisis to practice. When you notice mild anxiety, frustration, or stress:

Pause and regulate first (30 seconds to 2 minutes of body-focused intervention)

Then engage cognition (What’s actually happening? What story am I telling? What do I need?)

Finally, take aligned action (What’s one small thing I can do right now that aligns with my values?)

Practicing this sequence when stakes are low builds the neural pathway for when stakes are high.

**Step 4: Challenge “Thinking Will Fix It” Beliefs

Notice when you catch yourself trying to think your way out of a body-based response. Common thoughts include:

“I just need to be more rational about this”

“I should be over this by now”

“If I understood it better, I wouldn’t feel this way”

When you notice these thoughts, gently redirect: “This is a body response. I need to regulate first, then I can think about it.”

Step 5: Work with a Trauma-Informed Professional

If you’ve experienced significant trauma, working with a therapist trained in both somatic and cognitive approaches makes an enormous difference. Look for practitioners who mention:

Somatic Experiencing (SE)

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy

Trauma-Focused CBT (not standard CBT)

Polyvagal-informed therapy

Internal Family Systems (IFS)

At Your Kind of Happy LLC (yourkindofhappy.org), we specialize in integrating neurofeedback, EMDR, somatic regulation, and cognitive processing specifically for trauma, TBI, and performance optimization. Whether you work with us or another provider, seek practitioners who understand this mind-body integration rather than treating them as separate domains.

Step 6: Measure Progress Differently

Stop measuring healing by how often you feel triggered. Instead, measure:

How quickly you can regulate when triggered

How much compassion you have for your responses

How often you catch yourself before dysregulation escalates

How well you can distinguish past danger from present safety

How much you trust your body’s signals rather than fighting them

These metrics reflect actual nervous system healing, not just symptom suppression.

The Bigger Picture: Redefining What Healing Means

For too long, mental health treatment has operated under an implicit assumption: that the mind is primary and the body is merely its vehicle. That thinking correctly will create feeling correctly. That insight equals healing.

This assumption fails spectacularly with trauma because trauma isn’t primarily a disorder of thinking — it’s a disorder of the nervous system’s ability to distinguish safety from danger.

Healing trauma means restoring your body’s capacity to feel safe in the present rather than remaining perpetually braced against threats that no longer exist. It means rebuilding the communication pathways between body and mind that were severed or damaged during overwhelming experiences. It means learning to interpret your body’s signals as information rather than enemies.

This isn’t a lesser form of healing or a temporary patch until “real” (cognitive) therapy can occur. It is real healing — perhaps the most real kind, because it addresses the foundational dysregulation that makes all other interventions less effective.

When Sarah finally understood this, her entire relationship with recovery shifted. She stopped berating herself for not being able to think her way out of panic. She started noticing the early warning signs in her body and intervening with regulation tools before full-blown activation occurred. She practiced differentiating between “old alarm” and “actual danger.”

Gradually, over months, her window of tolerance expanded. The flashbacks became less frequent and less intense. She developed genuine confidence in her ability to manage her nervous system rather than feeling victimized by it.

Most importantly, she stopped seeing her body as broken or defective. She recognized it as an exquisitely sensitive instrument that had kept her alive through impossible circumstances and was now, slowly, learning to trust that the danger had passed.

That’s the promise of integrating bottom-up and top-down approaches: not that trauma never happened or that its effects disappear completely, but that you develop genuine agency in your own nervous system. You learn to work with your body’s protective wisdom rather than against it. You become the compassionate interpreter of your own experience rather than its harsh critic.

Conclusion: The Body Remembers, The Mind Integrates

Here’s what I want you to take away: You are not failing at recovery because thinking alone doesn’t work. The system isn’t designed that way.

Your body’s responses make sense. They’re not random, not weakness, not evidence of being broken. They’re the echoes of protection, the residue of survival, the nervous system doing its job with outdated threat information.

The solution isn’t to think harder or understand more deeply. It’s to speak the language your body understands: breath, sensation, movement, rhythm, and felt safety. Once you do that, once you can genuinely settle into your body rather than perpetually bracing against it, then all those cognitive tools you’ve learned become genuinely effective.

Healing happens in layers:

First, we learn to regulate the body

Then, we can reflect with the mind

Finally, we reframe the meaning and integrate the experience into our story

This isn’t a linear process. You’ll move back and forth between these layers many times. Some days will require more body work, others more cognitive processing. That’s not failure — it’s the natural rhythm of integrated healing.

If you’ve spent years trying to think your way out of trauma and wondering why it isn’t working, I hope this article provides both explanation and relief. You weren’t doing it wrong. You were using an incomplete map.

The complete map acknowledges that emotions begin in the body, are processed by the body, and must be addressed through the body before cognitive work becomes truly effective. Once you understand this, you can stop fighting against your own biology and start working with it.

Your body has been trying to tell you something important. Perhaps it’s finally time to listen.

About the Author

Dr. Matthew McKeithan, Psy.D. (CA License #34462) is a clinical psychologist and founder of Your Kind of Happy LLC and BrainFit Studio. He specializes in trauma-informed neurofeedback, cognitive-somatic integration, and evidence-based psychotherapy for TBI, PTSD, anxiety, and performance optimization. Dr. McKeithan integrates cutting-edge neuroscience with compassionate clinical practice to help clients understand and regulate their nervous systems. Learn more at yourkindofhappy.org.

References

Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York: Putnam.

Levine, P. A. (2010). In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Lieberman, M. D., Eisenberger, N. I., Crockett, M. J., Tom, S. M., Pfeifer, J. H., & Way, B. M. (2007). Putting feelings into words: Affect labeling disrupts amygdala activity in response to affective stimuli. Psychological Science, 18(5), 421–428.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Van Der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York: Viking.